- Home

- About

- Stakeholders

- Projects

- Water

- Evaluating reservoir operations and the impacts of climate change in the Connecticut River Basin

- Collaborative development of climate information for the Connecticut River Basin using Shared Vision Forecasting

- Impacts of climate change on the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority water supply system

- Climate information for water harvesting and re-use strategies in urban settings

- Delaware River streamflow reconstruction using tree rings

- Coasts

- Health

- Cross-cutting theme: Climate

- Cross-cutting theme: Vulnerability/Evaluation

- Water

- Library

- Resources

- Seminars

- Contact Us

The Future: Adaptation and Mitigation

With a high quality of educational and public-health institutions, overall wealth, and large amounts of “scientific capital”, the cities of the Northeast have the ability to both adapt to and combat the challenges of climate change. The cities of the Northeast corridor are interconnected, and with that, so are their governing bodies. Municipal governments will have to be more dependent on one another for financial and infrastructural support during times of environmental transition.

The human response to global climate change and climate variability can be characterized in two ways: Adaptation and Mitigation. Adaptation involves developing ways to protect people and places by reducing their vulnerability to climate impacts. Examples of adaptation include building seawalls and providing public health services for those most vulnerable to the impacts of weather extremes. Mitigation involves attempts to slow the process of global climate change by lowering the level of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Examples include such mechanisms as planting urban shade trees to lessen the need for air conditioners.

We must face the reality that large public projects require bidding wars, extensive approval processes, and an allocation of funds, procedures that are inevitably lengthy. Climate change will not wait for the government to catch up, and thus it is essential that regional governments wait no longer to implement adaptation and mitigation strategies.

Please click on the questions below to expand and collapse their answers.

Adaptation: Preparing for the Future

In this section we examine what people are currently doing or could do in the future to adapt to climate change, as we have learned that this process is inevitable. When discussing climate risk adaptation, it is essential that the vulnerability and limitations of certain populations are explicitly addressed. Information on what public institutions within the region are doing to prepare for a changing climate is presented. We also describe what private companies in the region are doing to prepare for climate change. How individuals in the region can respond and adapt to climate change impacts is discussed. Where possible, the costs of adapting to global climate change are presented as well.

How can we determine a community's capacity to adapt?

It is clear from the number of Nor’easters that occurred throughout the 1990s and the flooding in 2006 that the Northeast’s natural and social systems are vulnerable to weather extremes. A lack of vegetation, high energy consumption, and high material absorption makes the region’s dense cities particularly susceptible to the impacts of climate change. Continued reliance on existing infrastructure and public policy is insufficient in preparing for future climate risks. Changes must start immediately. What we must now assess is the region’s ability to cope with and prepare for these extreme conditions and the ones that have yet to come. The Northeast is very diverse with regards to physical, environmental, and socio-economic qualities. Due to this, communities’ adaptive capacities must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with the help of a wide variety of constituents, including government officials, the private sector, and society. This section proposes a flexible framework to assess a specific community’s ability to adjust to the impacts of climate change.

![]()

The above map shows vulnerability to climate change impacts in the Northeast. Vulnerability is defined here by an accumulation of various factors: access to material resources/lifelines, the built environment, access to information/experience, and the population densities of children, persons with disabilities, the elderly, and African-Americans. Source: Cox et al, Index of Social Vulnerability in Social Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Neighborhood Analysis of the Northeast U.S. Megaregion, 2006

Evaluate the range of technologies available to cope with climate-related stress on the environment and the people.

Technology offers a powerful tool to cope with the changing environment, and it will only advance as time goes on. This includes building new protective seawalls, creating crop varieties that can flourish in a warmer climate, and advancing snow-making abilities for the winter recreation industry. We must make sure that these technologies are available for communities to use. Failure to adjust to climate change will hurt the regional economy across the board, from the apple orchards to the lumber yards to the fisheries to the ski slopes. Although technological adaptations will come with additional costs and risks, it will help these industries survive. Yet when discussing these possibilities, we must also consider the potential environmental and economic burdens that these developments would have on the physical and social landscape. An extensive cost-benefit analysis would be very useful in this situation.

Recognize and accommodate for demographic differentiation and social injustices in order to distribute resources proportionally across the population.

Differentiation in individuals’ abilities to adapt to extreme events and climate change are created by varieties in income level, race, education, and age. It also occurs because individuals have diverse access to health insurance, which becomes more of an issue as the number of heat-related stress and fatalities increases. The Congressional Black Caucus Foundation (CBCF) has stated that “the increasing reliance on [expensive forms of] adaptation (e.g., healthcare and air conditioning) is likely to create a larger disparity between mortality of the rich and poor.” Even in a region as wealthy as the Northeast, we have a moral obligation to help the most vulnerable communities if we want to sustain the region both ecologically and economically. It is essential that these realities are explicitly accounted for in the discourse of climate change adaptation.

Measure the ability for critical institutions’ structures and policies to adjust for a changing climate.

Local institutions will be required to make changes in policy and decision-making structures as the environment and physical make-up of their cities transform. Some possible alterations include changes in land-use planning, newly implemented wetland protection regulations, construction that abides by certain environmentally-conscious standards, and restrictions on coastal activities. Changes in policy and a reallocation of funds based on projected risks rather than historical events may disrupt the status-quo that many individuals in the realm of development, private business, and recreation would rather maintain, yet these adjustments are necessary if we are to adequately accommodate for our changing physical landscape.

Assess scientific capital, decision-makers’ ability to manage information, and the credibility of the decision-makers themselves.

The Northeast has tremendous academic capital, with its countless educational and health research institutions. Having such scientific capacities makes the area vital for climate change research both globally and locally. In order for this research to have meaning, it must be able to easily reach government entities, the private sector, and the general public. Some sectors, like agriculture and forestry, have already begun to utilize this information. The majority of constituents though, lack sufficient information about the issue, creating uneven adaptive capacities throughout the region. It is therefore the responsibility of researchers to transfer their findings to outside groups who will then steer decision-makers in the right direction.

Judge public understanding of the issue and prepare them for changes accordingly.

The wider public must be informed that a warming climate is inevitable, and therefore adaptive measures must be taken. Although recent polls have recorded an increase in overall awareness and concern about climate change, citizens need to know how much this warming will affect essential parts of their lives, such as their lifestyle, overall health, and property. Not being conscious and prepared for these changes will make adjustments to climate change much more difficult.

The above map shows vulnerability to climate change impacts in the Northeast. Vulnerability is defined here by an accumulation of various factors: access to material resources/lifelines, the built environment, access to information/experience, and the population densities of children, persons with disabilities, the elderly, and African-Americans. Source: Cox et al, Index of Social Vulnerability in Social Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Neighborhood Analysis of the Northeast U.S. Megaregion, 2006

What are public agencies doing in the region to adapt to climate change?

Public agencies on the federal, state, and local levels have begun planning to help the urban Northeast corridor adapt to the impacts of climate change. Federal agencies should take the lead in adaptation to encourage action at the regional level, yet there have been many instances, such as the ones explained below, where municipal governments have initiated programs on their own. The integration of climate change into stakeholder decision-making takes two forms: considering the environmental, human health, water management, and infrastructure issues associated with a changing regional climate when making decisions, and initiating inter-agency communication, educational and outreach programs and capital reinvestment to raise awareness of the problem.

Federal:

The Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) carries out numerous projects around the Northeast region that aim to counteract beach erosion, reduce flood damage, and restore natural wetlands and estuaries, some of which explicitly include climate change. The Fire Island Inlet to Montauk Point Reformulation Study in New York, for example, includes sea-level rise due to climate change in their models of future conditions.

Boston:

The Boston Indicator’s Project, a partnership between the Boston Foundation, the City of Boston, and the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, attempts to make information more accessible, encourage informed discussion amongst citizens, and identify mutual interests within the community. Stakeholders come from a wide array of agencies and sectors. This enables leaders of the Project to emphasize the multidimensional nature of global climate change, such as the connection between the urban heat island effect and an increase in human heat-related stress. By connecting readers to key information resources in its online outreach, such as the Northeast Climate Impacts Assessment and the Climate’s Long-Term Impacts on Metro Boston (CLIMB) Project, the Boston Indicator’s Project not only educates citizens about the regional effects of climate change and the value of environmental stewardship, but also connects them to other relevant resources, further expanding their knowledge of the topic.

New York City:

The Division of Coastal Resources of the New York State Department of State, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) Division of Wildlife and Marine Resources Bureau of Marine Resources released The New York State Salt Marsh Restoration and Monitoring Guidelines, which notes that sea-level rise due to global climate change threatens salt marshes. They suggest identifying and protecting low-lying areas to allow future landward migration of salt marshes. They describe methods of restoration that make wetlands more resilient to both sea level rise and natural disturbances. Also in New York State, the Long Island Sound Coastal Management Program of the Department of State created Executive Law §913, which states that developers must consider sea-level rise when siting and designing projects involving substantial public expenditures.

Philadelphia:

Boston and New York City can use Philadelphia as a model for successful public health adaptation practices. In 1995, the city’s Department of Health implemented a new system of public health interventions to combat its apparent reputation as the “heat death capital of the world”, focusing on susceptible populations such as the elderly, poor, and homeless. Some examples of programs include conducting home visits to the elderly, increasing the number and operating hours of public cooling stations, and encouraging a Buddy System where citizens check on older friends and family during heat waves. While every inhabitant is affected by the current and future climate extremes, Philadelphia’s recognition and accommodation for certain populations’ limitations provides an example for progressive public service.

What can the private sector do to adapt to climate change?

Multinational corporations and regionally-based business coalitions are beginning to address adaptation to climate change. Corporations taking the lead tend to be financial institutions, particularly insurance companies. The urban Northeast corridor has a relatively open economy, with goods and services freely flowing in from and out to all corners of the world. Climate change would potentially disrupt this flow by flooding transportation systems, leading to breakdowns in productivity. It is for this reason among others that the private sector leads the way for adaptation.

Private Sector Initiatives

The private sector has begun to address the issue of adaptation to climate change. Although many private sector activities are focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions through energy efficiency, such activities improve the region’s capacity to deal with warming in general and heat waves in particular. Most private sector activities to date have involved large multi-national corporations, many of which are based in the region, and/or coalitions of regional businesses and associated trade or professional organizations. The multinational corporations taking the lead in examining and in some cases responding to the threat of climate change are often financial institutions.

Regional Business Coalitions

As example of a regionally-based business coalition, the Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnerships (NEEP), a consortium of 38 New England gas and electric utilities, released the 2004 Business Plan to Support Regional Energy Efficiency Partnerships. The document not only outlines climate change action plans that have been instituted in New York and other northeast states, but also lays out plans for further climate change action strategies.

Multinational Corporations

One example of activities undertaken by multinational corporations is the U.N.’s Investor’s Summit on Climate Risk (ISCR). New York City was the site for the first meeting in November 2003 that focused on the effects of environmental regulations and future climate changes upon financial institutions. The Investor Network on Climate Risk was also created at that meeting. The summit resulted in a ‘call for action’ that was signed by both private pension fund managers and public officials, including former Comptrollers Alan Hevesi (New York State) and William Thompson (NYC). At the ISCR’s fourth meeting in January 2010, investors came to the consensus that the most feasible way to cut carbon would be to make it more expensive, enabling alternative energies like wind and solar to compete in the industry. The Investor Network is also affiliated with the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies (CERES), a coalition of investment funds, environmental organizations, and public interest groups that includes such organizations as the Sierra Club and the Fair Trade Foundation. CERES is endorsed by corporations like American Airlines, Consolidated Edison, and Bank of America.

Insurance Companies

Reinsurance companies, especially Swiss Re, are also addressing climate change issues and encouraging their clients to do the same. Swiss Re, along with the United Nations Development Programme and the Centre for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard Medical School, formed the Climate Change Futures Project, an international, multidisciplinary project designed to formulate future scenarios and their consequences based on a set of climate projections and development trajectories. The Climate Change Futures Project has sponsored several workshops and conferences with corporate leaders, scientists, and economists to integrate climate change understanding with public health, biological resources, and the long-term security of investments.

How can we adapt to the changing climate?

Whether we know it or not, we constantly make decisions that both contribute to and will be influenced by climate change. Successfully adapting to future climate change will require an understanding of its causes and likely impacts and, through this, of the ways to protect one’s self and one’s family. As individuals, we can have an impact on policymakers’ decisions that relate to climate change by becoming informed and engaged in the issue.

The Role of the Individual

As residents of the urban Northeast corridor, we all make decisions that contribute to future climate change. We depend on large-scale public energy and transportation systems that contribute to climate change through their greenhouse gas emissions. We may contribute to climate change through personal decisions about where to live and how to get to work, through our choice of appliances and patterns of water use. Yet, we also must understand how we are likely to be affected by climate change, how an increase in the frequency of storms, a rising propensity for floods, and a metropolitan transportation system that is dangerously close to the coastline could affect our lives in the future.

Gathering Information

The first step in taking action is to be informed. Just as public agencies cannot devise new policies without an understanding of the phenomena they want to change, so too we cannot make decisions without knowing what conditions are expected and what choices we have. Many websites produced by state governments and others provide information about the causes, impacts, and responses to climate change. See the Resources section of this website for more information.

Become Engaged in Your Community

Being informed can lead to taking action. Residents of the tri-state area have specific concerns about climate impacts, some of which are common to many urban areas and some of which are unique to the Northeast metropolitan area. There may be increases in the cost of electricity or homeowners’ insurance rates. Many homes and businesses are located in areas that will be prone to floods in the future. How will increased summer heat affect poor and elderly urban populations? There is often little that individuals can do in response to these projected impacts, but they can demand that urban policy makers take a long term view and recognize the need to plan ahead so that cities, counties, and states are prepared to meet the challenges posed by climate change.

Individuals can inform others about climate impacts through conversations, letter writing, attending Community Board meetings, and voting. What each of us does as an individual becomes amplified when we engage others in the discussion and persuade them that there is a need for a careful, reasoned response to the impacts of current and future climate change and variability. We can use our own understanding of the issue to promote appropriate policies in government, public utilities, and the private sector, all of which have an important role to play in how well the tri-state area responds to climate change.

Mitigation: Changing the Future

In this section, we examine why it is useful to focus on mitigation, what actions have been taken so far to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and what individuals and households can do to reduce their contribution to the issue.

Why is Mitigation important?

Although mitigation of climate change is a global process that will take centuries to make an impact, it is valuable to take certain mitigation steps now. Reducing the production of greenhouse gases in the region will result in immediate improvements in the regional environment and to economic efficiencies in households and businesses, and contribute to better health and well-being.

Why be concerned about mitigation?

At first glance, the most immediately useful and least economically disruptive response to climate change and climate variability is to develop strategies for adapting to and moderating those impacts that affect us most directly. Because climate change is a global phenomenon, this argument goes, and because it takes decades and even centuries for some greenhouse gases to disappear from the atmosphere, we should seek ways to deal with the local impacts of climate change and variability rather than trying to reduce it at the global level. Attempts to mitigate climate change could involve efforts that will take years and require concerted and expensive international cooperation.

For example, one of the principal means of mitigating climate change is reducing the production of greenhouse gases. Since mitigation strategies will only indirectly affect our local climate, many reasonable people assume that mitigation should not be a priority for the region. One problem with this approach is that if every city and country decides to give low priority to the mitigation of greenhouse gases, current trends in the global climate will continue and may even accelerate, causing more severe direct and indirect impacts in local areas.

A related problem is that focusing on adaptation to local impacts of climate change without attempting to reduce future changes to Earth's climate is not a responsible position for a city or region, a state, or a country. This is an issue of good governance and responsible stewardship of the Earth, not an issue that speaks to the self-interest of local governments or even the nation.

Near Term Benefits of Mitigation

Perhaps most important, giving low priority to the mitigation of future climate change ignores the reality that the reduction of greenhouse gas production is not useful merely because it contributes to the reduction of future global climate change. Mitigation strategies can have other extremely valuable collateral benefits for the Northeast region, benefits that are often overlooked. They include:

• Improvements in local environmental quality,

• Improvements in local public health and well-being, and

• Stimulation of the local economy.

In general environmental terms, reducing greenhouse gases can lead to an immediate improvement in the quality of the local environment. Air quality in the region could improve, bringing with it health benefits such as reducing the incidence of asthma and other upper respiratory diseases. Water quality could also improve, and public funds spent on improving water quality could be used for other beneficial purposes.

Many mitigative measures could have economic benefits for the region. In residential and commercial construction, sustainable building practices can lead to healthier indoor environments, lower energy use, and a reduction in pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. The creation of a more efficient and cost-effective public transportation system (one that is less dependent on the use of private automobiles) would also reduce emissions. Families might end up paying less for transportation and the region itself would be less dependent upon imported sources of energy. Switching from older, less efficient appliances to newer, energy-efficient appliances and technologies is another mitigation strategy that lowers energy costs for households and contributes to greater profitability for businesses.

These changes would be observable in a few years, certainly in decadal rather than century time scales. In a very real sense, mitigation of greenhouse gases would contribute to improving the regional environment, a benefit to be enjoyed in our lifetimes and those of our children.

What are members of the public and private sectors doing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions?

The Northeast needs to take a leading role in reducing CO2 emissions, as the region alone is the seventh largest emitter of carbon dioxide in the world. As a world leader in science, public policy and finance, the urban Northeast has the responsibility to lead the world in emission reduction. Many federal, state, and local governments, universities, and private enterprises have already started to explore reduction strategies, recognizing the seriousness of climate change and making efforts to save energy.

Models for Change

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a northeast regional plan, forces the electrical-power industry to cut emissions 10% by 2019. Beginning in January 2009, this is the nation’s first federally-mandated carbon “cap-and-trade” program. Many states have promised to auction all allowances from the program to energy-efficient programs, which would find their way back to the consumer in the form of employment, energy security, and savings on personal energy bills. A parallel resolution is the New England Governors and Eastern Canadian Premiers Climate Change Action Plan of 2001, which committed states and provinces in the region to reducing emissions 80% by the end of the century.

The Staples Corporation created a second rooftop solar panel system in January 2007. It is almost the size of one and a half football fields, or 74,000 square feet. This renewable energy system is responsible for around 15% of the company’s annual electricity. That number may not seem large, but Staples’ actions provide a stepping stone for environmentally-conscious initiatives in the corporate world.

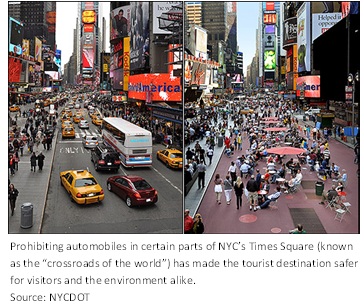

In 2007, the New York City government created PlaNYC, a multidimensional, sustainable initiative committed to strengthening the local economy, improving overall quality of life for its residents, and battling the changing climate. Since its inauguration, PlaNYC has planted almost 500,000 trees, created pedestrian-only zones (including one in the middle of Times Square), retrofitted 100 public buildings to higher energy-efficiency standards, and launched a bus rapid transit system, among many others. Mayor Michael Bloomberg has promised to make 13,000 city taxis hybrid by next year. These methods have enabled the city to come closer to its goal of reducing energy use 30% by 2017.

Cornell University sets an example for smart private investments in public transportation with its Transportation Demand Management Program. Through an arrangement with the government of Ithaca to enhance the region’s transit system, the university has been able to save tens of millions of dollar in building and infrastructure costs while simultaneously helping the environment.

What can individuals in the region do to slow down climate change?

Individual actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions can help slow down climate change. Many actions have synergistic, or "win-win" effects. Choosing modes of transportation, new appliances, and building materials that are energy efficient can often save money in addition to reducing emissions. Planting shade trees can both reduce emissions and raise property values. Governments have begun participating in the fight against climate change, but there is still much more to be done. Engaging with decision-makers can enhance the impact of individual actions.

Transportation

The transportation sector accounts for the most greenhouse gas emissions throughout the region. By choosing to drive less, form carpools, ride a bicycle, or use public transportation, individuals can reduce their contribution to the release of greenhouse gases. Currently, twenty-five pounds of greenhouse gas is emitted for every gallon of gasoline we use. Individuals can help scale back that incredible amount by purchasing cars with greater fuel efficiency. This purchase would not only lessen an individual’s ecological footprint, but would also save them thousands of dollars at the pump. Those who travel frequently by airplane may also want to consider that air travel is one of the fastest-growing sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Transportation of non-local foods to local supermarkets, and transportation of waste to landfills and/or incinerators are also substantial sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Purchasing local foods and attempting to reduce waste thus also reduces an individual's contribution to emissions.

Home and Neighborhood

Many strategies for reducing home energy use can cut greenhouse gas emissions and also save money when reduced energy use translates into lower energy bills. Individuals can choose to purchase energy-efficient home appliances, electronics, office equipment, and light bulbs. While the up-front costs for these products may seem higher than conventional products, lower long-term operating and maintenance costs make them smarter purchases in the long run. The Department of Energy and EPA Energy Star program maintains an extensive list of energy efficient products. People can also improve the insulation in their homes to reduce energy required for heating and cooling, add skylights to improve natural lighting, or consider solar panels, a reflective roof or a vegetated roof ("green roof").

Finally, residents with open space around their homes can plant deciduous shade trees in strategic locations. City-dwellers without yards can help to start or support neighborhood tree-planting programs. Shade trees can help reduce cooling bills in the summer. In addition to reducing energy needs, trees can also store carbon dioxide and remove pollution from the atmosphere.

Slowing Down Climate Change

The burning of fossil fuels to produce energy and power automobiles, deforestation from the harvest of timber products, and the conversion of naturally-vegetated land to urban, suburban, and agricultural areas have increased the concentration of greenhouses gases, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2), in the atmosphere. Individuals can slow down climate change by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases associated with their daily energy consumption in the home and on the road. Because each molecule of CO2 remains in the atmosphere for ~100 years, reducing emissions today will continue to have an impact on concentrations of CO2 for long time periods. These actions can help to slow climate change over decadal and century-long scales. Three main areas in which individuals can take action relate to transportation, the home, and the neighborhood.

Engaging with Decision-Makers and Others

Those who are concerned about the impacts of climate change on their communities can express their concerns at community board meetings, by voting for politicians who share their views, by contacting elected officials, and by investing in companies that take a progressive stance on climate change. Citizens should pressure officials into strengthening renewable electricity systems, adopting low-carbon fuel standards, rezoning areas for more sustainable development, and improving appliance efficiency standards. Engaging decision-makers, as well as local businesses and neighbors, is an important step to reducing a community's contribution to climate change.

Get printable versions here.